Richard Vedder fondly remembers the days when university professors had the closest thing to full ownership of their classes, including what they taught and when they taught it. Of course, school deans might have had a say or two in the material and provided some basic guardrails — like requiring a minimum number of classes. But overall, most of Vedder’s 50-year career as a business professor came with the freedom to customize his material and choose his schedule.

Vedder, now 83, for decades would occasionally mail a course syllabus to the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), which helped maintain the reputation of the schools where he taught, including the Claremont Colleges and Washington University in St. Louis. He never felt any inconvenience from handling the accreditation, though, nor any real pressure from his bosses to do so.

“My first 30 years or so of teaching offered a great deal of freedom and influence,” explained Vedder, now a distinguished professor of economics emeritus at Ohio University. “We wore more hats back then, but I felt the autonomy gave us a greater stake in our departments and a greater sense of pride in our work as a whole.”

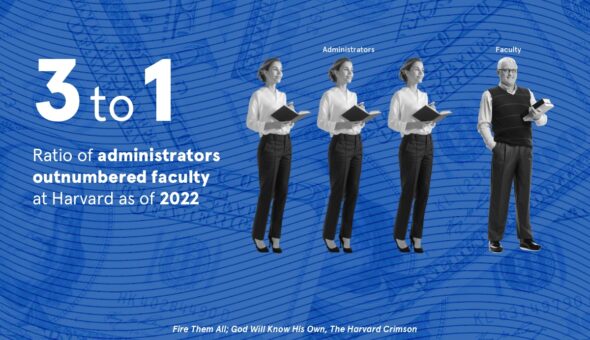

Unfortunately, those days are long gone. Handcuffed by an ever-growing list of accreditation bureaus, guidelines on coursework and institutional bloating that has delegated more work to administrators, professors like Vedder are less connected with their schools and perhaps less influential than ever. More importantly, universities are paying the inflated costs of keeping up with accreditors and passing those costs onto increasingly price-conscious students.

Accreditation has become significantly more complex in recent decades and now requires more employees for universities to handle the process, explained Vedder. The addition of new accreditors in every field and specialty during the past few decades has also left universities and their staffers with more red tape. But as the cost of higher ed reaches new heights and more high-school students reconsider whether a university education is worth the price, could the accreditation circus and institutional bloat be reaching its tipping point?

Like everything in today’s higher ed landscape, the answer is complex.