When coaching great Nick Saban retired from the University of Alabama before the 2023-24 college football season, it seemed to mark the end of an era. The hard-nosed, old-school brand of college coach who recruited athletes and wooed families on the promise to develop young men into future leaders appeared to give way to younger, more affable coaches that could promise big Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) paychecks and guaranteed playing time.

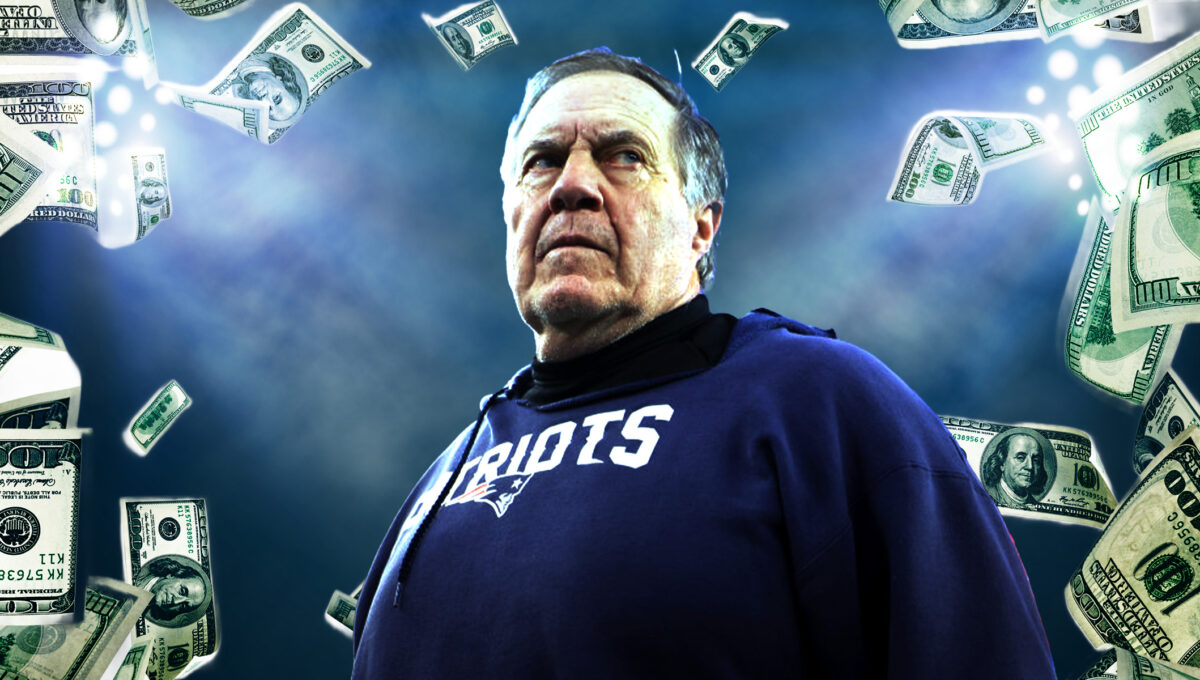

Then, out of nowhere, the NFL’s most decorated head coach entered the fray. In December, Bill Belichick, the six-time Super Bowl champion with the New England Patriots, agreed to coach the University of North Carolina — a middle-tier ACC football program better known for its iconic basketball teams. The price? A whopping $50 million over five years. UNC’s athletic director called the hire an “absolute perfect fit” as part of the school’s plan to make an unprecedented new investment for its football team to become a winner.

The hiring of the sport’s most successful and traditionally no-nonsense head coach came with serious caveats, though: Belichick needed to adapt to the new landscape of college sports, win games and, above all, help the school make money.“

We’re investing more in football with the hope and ambition that the return is going to significantly outweigh the investment,” said UNC AD Bubba Cunningham during an introductory press conference in December. Cunningham also budgeted $40 million to hire a front office staff and give raises to Belichick’s assistant coaches. “We do see the future of college athletics as very dependent on a successful football program.”

But can UNC really earn that much money back from such exorbitant new spending? If so, where will they get it from? Both answers are complicated, experts said, especially after an offseason that became unexpectedly filled with off-the-field drama and almost-immediate doubt over whether Belichick will even still be UNC’s coach by September’s opening kickoff.

Offseason Drama and Doubt

A full year removed from his departure in New England, Belichick reportedly wanted to return to coaching in the NFL in the weeks before and perhaps even after he signed with UNC, as rumors in January linked him to the Las Vegas Raiders. Reports then leaked of tension and confusion among Tar Heels’ brass, which prompted Belichick to publicly (and uncomfortably) confirm through the program’s general manager that he wasn’t leaving the university.

David Aaker, who serves as vice chairman of San Francisco-based consulting company Prophet and taught for over four decades at Cal Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, believes Belichick’s offseason drama is more of a “neutralizing factor” than full-blown chaos.

“The focus should be on his amazing career, his knowledge base and ability to coach,” Aaker said. “But someone has changed the conversation and it’s impacting his ability to get positive press. If I was North Carolina I’d be more worried that it’s a different discussion that’s taking the spotlight away from his credentials. It’s not as much as they have a bad thing going as much as the good thing they had going has receded.”

Huge Salaries and Enrollment Gains

Just months after the school hired Belichick, Cunningham announced that UNC had sold out the 20,000 season tickets it allotted for 2025 at Kenan Stadium, the Tar Heels’ home field. That’s after jacking up prices by about 25% per seat, from an average of about $700 in 2024 to $875 for the coming season. Ticket revenue for those seats alone will account for some $3.5 million in added proceeds compared to last season, possibly doubling season-ticket revenue given that the school didn’t come anywhere close to selling out its season tickets in 2024. Not to mention that significantly more fans in the stands mean more people buying concessions and merchandise at each game.

If I was North Carolina I’d be more worried that it’s a different discussion that’s taking the spotlight away from his credentials. It’s not as much as they have a bad thing going as much as the good thing they had going has receded.” — David Aaker

UNC’s application and enrollment figures also reached record highs for the upcoming freshman class, which Tar Heels sports administration professor Nels Popp credits, at least in part, to the Belichick effect.

But even the extra tuition dollars, ticket revenue and purchases by new students and fans, are still a drop in the bucket compared to the astronomical annual cost of Belichick and his staff, Popp argued. Belichick’s predecessor Mack Brown earned less than half each year of what the former NFL legend will make, and total expenditure for UNC’s entire football staff was only $13.1 million last season.

Ticket sales, advertising revenue and booster donations will need to multiply two-fold or more just to cover costs, said Popp, who’s taught at UNC since 2014.

“It seems like a good coaching move, but financially it’s going to be very tough,” he told Volt. “Our football stadium seats 50,000; it’s not like Michigan or Tennessee or Penn State that seats over 100,000. So when tickets sell out, there’s a cap on what you can do.”

Popp acknowledged the importance of alumni and booster donations to UNC’s bottom line, but speculated that donor fatigue in the wake of a landmark NIL settlement may limit their generosity this season. UNC’s 17,000-member Ram’s Club booster collective recently announced its plans to cover $20.5 million in annual revenue-sharing required by last month’s federal NIL ruling, as part of an average $70-$80 million it gives to UNC athletics each year.

Popp said the arrival of a new football coach, even of Belichick’s caliber and cost, still may not move the needle for donations at a traditionally basketball-minded school.

“It ultimately comes down to, when you double what you’re paying your coaching staff, can you double your revenue?” Popp said. “That’s a big ask. I’m not saying it can’t happen, I’m just saying it’s not as compelling of a case as it was before the NIL era.

“I can see that playing well at Alabama or LSU where everyone lives and breathes football 365 days a year,” he added. “But because that’s not the history here, there may not be as much appetite for donating to make sure we get the best left tackle in the country.”

Winning Cures All?

Both Popp and Aaker agreed that Belichick can exorcise his PR demons with one feat: winning on the field. If the Tar Heels improve from last season’s 6-7 record and earn a bowl-game victory, the momentum heading into Belichick’s second season could result in more nationally televised games, sponsorship deals and donations for the Tar Heels. In the unlikely event UNC bests any or several of traditional ACC powers like Florida State, Clemson, Virginia Tech, Miami and SMU for this year’s conference championship, Belichick would almost certainly be named national coach of the year and on his way to building a powerhouse program.

“The good news for him is the bar is a little bit lower at UNC than for a Alabama or a Michigan or a Notre Dame,” Aaker said. “He still has to win, but there’s not that ‘national championship or bust’ mindset.”

On the other hand, a rocky season with a losing record could diminish the excitement surrounding UNC football, leaving the school with an overpaid staff, little support and serious bills to work through. Popp compared the consequences of a poor first season to what eventually happened under Mack Brown, the university’s once-hyped former coach who also had a championship pedigree.

“People just lost interest,” Popp said. “I do think Belichick’s reputation and credentials give him a bit of a longer leash. But the narrative surrounding the girlfriend is fascinating. If he wins, the naysayers will probably come back around and maybe even credit some of his success to being with her. If he loses, all the talk will be about how he wasn’t focused enough and how she brought him down.

“Working in sports and athletics, you have to have thicker skin for that. We’re such a public industry that everybody has an opinion. The marketing situation probably isn’t ever as bad or as good as people off the field make it seem.”