Burnout vs. Cost

Laurel Williamson, deputy chancellor and president for San Jacinto College, a community college in Pasadena, Texas, shared that approximately 75% of the college’s students work part-time or full-time while attending classes. The institution also offers work-study opportunities on and off campus.

“For our area and student demographics, it is very common for students to need to balance their class schedule around their work schedule,” said Williamson. “We encourage students to work within what they can manage within their busy lives.”

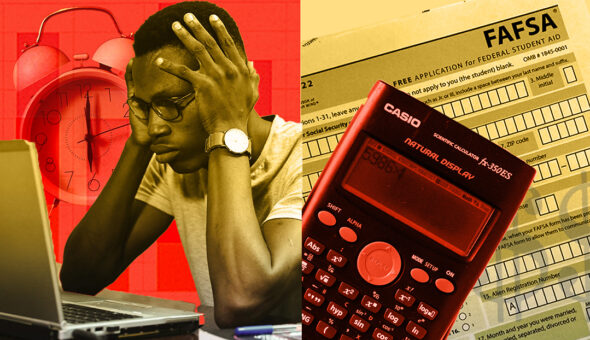

According to Williamson, she has found that first-time-in-college students often underestimate the demands of going to college and try to take more classes than their busy schedules allow.

“We want their beginning semester to be a successful one, so we work with students to develop reasonable schedules that they can manage,” she said. “These initial successes are critical in whether or not a student continues in higher education.”

Swami, who scheduled classes before realizing the need to work part-time, agreed.

“If I had to complete my undergraduate schooling again, I probably wouldn’t have saved four difficult bioengineering concentration classes for my final semester,” said Swami. “I didn’t know I would be working during my final year when planning my classes out for my four years, and I wish I had given myself some more ‘cushion’ classes for my last semester.”

Other students know from the outset that they will need to work to offset the cost of their degrees. “Dee”—a New York University Stern School of Business graduate who wishes to remain anonymous—pursued a 1-year, focused MBA, graduating in May 2022. Dee worked full-time as a program manager during her studies, logging 30 to 35 hours a week at a prominent software company while completing 30 hours of class a week.

“I didn’t want to be in six-figure debt when I completed the program,” said Dee. ‘“I was paying for the program completely on my own and it was a goal that I had always had.”

Remarkably, she was the singular student in her NYU cohort of 50 who worked full-time the entire year. In reality, MBA students in her program were encouraged to not work and just focus on school because the program was already accelerated from two years down to one. However, some institutions are beginning to recognize the need for flexible programs.

Maria Lemaire, 25, completed an M.S. Ed in Literacy (Birth-Grade 6) at Hunter College while serving as a head preschool teacher in New York City. Luckily for Lemaire and many of her classmates, NYS and NYC piloted an Early Childhood Workforce Scholarship for teachers who worked at least 20 hours a week and attended public universities to pursue further relevant education.

“Most of my degree was paid for by the city and state due to me qualifying through my work and the degree I was working towards; it paid for the majority of my tuition while pursuing my degree because it waived six credits of classes each semester,” said Lemaire. “The program was then amended to provide up to $4,000 annually. It was a tremendous help, and I think this program should be implemented nationally to all public service professions.”