In “The Clock of the Long Now” Stewart Brand wrote, “Fast gets all the attention. Slow has all the power.” Although an excellent description for complex systems like culture and governance, it’s also an interesting lens to view the current state of higher education marketing. We’ve fallen in favor of what I am calling fast media, while not balancing slow media—to the extent that we’ve essentially cut our marketing funnels in half. It’s time that we revive the funnel and learn to balance what we prioritize across it.

It’s not hard to see why we’ve ended up here. Like higher ed, most industries have grappled with the dynamics of performance versus brand or digital versus traditional or whatever marketing debate creates a diametrically opposed set of concepts. The promise and subsequent praise of most digital advertising is that it gives us real-time, hyper-targeted and perfectly attributed tools that allow the marketer to operate at peak efficiency—the fast.

Yet, we know that advertising doesn’t necessarily work that way.

In many ways, advertising’s impact is felt in the long term and incurs a cumulation of effects. It primarily influences behavior by building and reinforcing memories to help a brand come to mind easier. In the case of higher education, it’s often the slow that helps affect one’s consideration set prior to being in-market. So, when we use terms like build or increase awareness, we are introducing the slow—among other brand-building endeavors, such as influencing price sensitivity and brand consideration.

What I would argue is that we’ve relied too much on the fast, and in this over-reliance, we’ve essentially cut our marketing funnels in half, missing out on the marketing effectiveness the slow brings. We’ve signified the value in the immediate and real-time, so we balance our budgets in favor of it. In doing so, we’ve neglected the majority of the market we hope to influence.

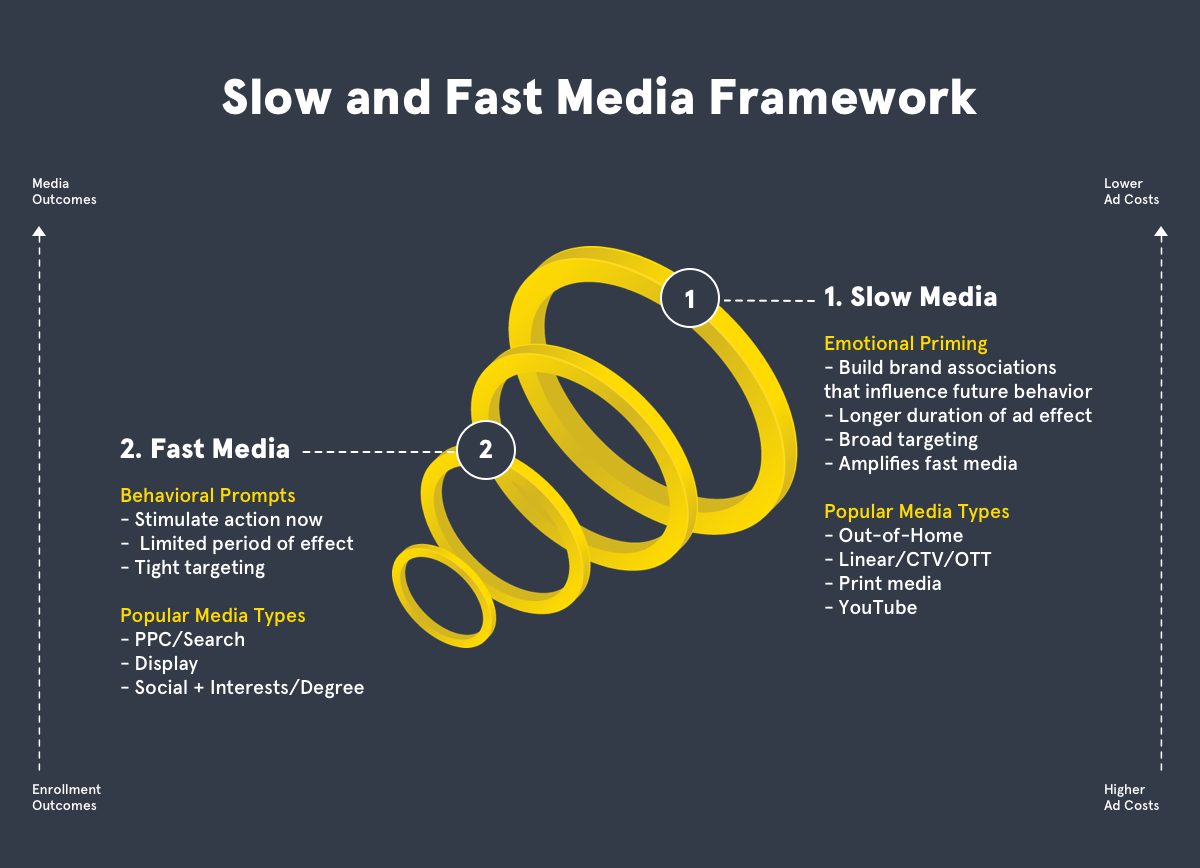

To be clear, this isn’t an indictment of digital advertising. It’s about media choice and effect. It’s about activation versus brand, sales and saleability. Fundamentally it’s about balancing both. As Claire Strickett argued, our media choices inform the breadth of our targeting, as well as our proximity to the purchase and what objective we are hoping to achieve.

Fast and slow gives us a frame of reference that brings clarity to why and how we should treat our media choices. Before we dive into what I’ve called fast and slow media, let’s first look at why this distinction is important.

Market and Media Realities

Technology has not only changed the way we consume content but has caused exponential growth in choice. Coupled with this growth comes audience fragmentation, creating unique challenges for marketers to not only gain attention but also build effective brand messaging and understand the effectiveness of our media choices. This sense of rapid change and the increasing number of measures associated with each channel, combined with the fast-paced environments in which we operate and our perception of optimized performance data has narrowed our focus on media choices that prioritize immediacy. What we know, and this can be especially visible in high-involvement categories, is that we are quick to reach a performance plateau. We must have a balance of slow media because of the following factors.

Education is a high-involvement category. The path-to-purchase is long, and consideration sets are formed well in advance of a purchase decision. What this really means is that yield is year-round and our media choices should reflect the long-term nature of most prospective students’ decision-making processes.

The middle is messy. The customer journey is messy at best; attention is divided; and interactions with brands extend beyond our control–making higher education marketing much more difficult. Furthermore, growing research indicates that search effectiveness is mostly driven by brand awareness. Consumers use search ads as navigational aids, like rented space on a salesroom floor. It’s been well documented that the best way to improve direct response rate (Google Ads/SEO) is to add brand communications to the mix.

Media is fragmented. Media fragmentation has caused many of us to spend more on martech, increased our production costs (more assets/less media), scattered our messaging and reduced our reach; all to place our effects into an attribution model designed to give credit to its own ecosystem (Your video ad may do all the work, but your search ads will get all the credit).

The cost and competition of digital advertising have increased. We’ve entered a world where CPMs are part of a live auction and platforms are beginning to charge a premium to access it. Across social media, CPMs have risen by some 33%. We are reaching a point where digital is no longer the cheap panacea we’ve come to enjoy, making a better case for a balanced media mix.

Clicks don’t always correlate. If you really think about it, the click is the least likely behavior our audience will exhibit. So much of what happens once an ad is delivered happens outside of the ad unit—a powerful reminder for high-involvement categories. Similarly, when we rely on a narrow set of attribution measures, we miss the forest for the trees.

Fundamentals of Fast Media

“Long-term results cannot be achieved by piling short-term results on short-term results.” — Peter Drucker

Fast media prioritizes an immediate response. Amazon, Google, Facebook and so forth have given marketers a wonderful set of tools that allow advertisers to target millions of users with direct-response advertising. These really are unprecedented capabilities when it comes to affordable media, audience targeting and in-platform measurement.

The problem with fast media is that the usual methods of employing highly targeting, bottom-of-the-funnel ad choices are diminishing its effectiveness, as the quantity and quality of the data we collect are becoming increasingly restricted.

Both value and reliability have been reduced. Value in the sense that we’ve only captured existing demand, and as our campaigns progress, those audiences become increasingly expensive, driving cost-per-acquisition cost upward. In a bidding system that uses keywords, clicks or impressions, whoever bids the most wins. Advertisers enter a circuitous loop of trying to gain a foothold in short-term response over future growth as cost increases.

In terms of reliability, iOS14, ad blocking and the weakening of behavioral signals across many of the platforms we employ mean our measurement systems are built on a narrow slice of the platform pie, aimed at a select few and optimized in a way that demonstrates singular value and doesn’t consider the extent of all advertising efforts. As we’ve lived through a few quarters of lost signals, we are seeing the platforms themselves tell advertisers to go broad.

Fast media has its place, but it’s meant to only affect one part of the funnel.

Fundamentals of Slow Media

“The most powerful brand advertising can create attractive associations for brands that last for decades, making them immensely valuable assets.” — Peter Field

The problem with slow media is that it can be seen as a risk and hard to measure. Risky in the sense that immediate impacts are rarely felt and that we are assessing results in a less-direct measure. Although advertising should be seen as an investment, future results can be a hard sell as our category constricts and economic uncertainty looms.

In terms of measurement, not only are slow media results long-term but the measurements most often used to assess awareness take planning and strategic implementation, usually in tandem with multiple partners or departments.

Yet, we know slow has power.

The high-attention potential of slow media, such as CTV/OTT and OOH, has the power to command more attention. More attention leads to better recall and priming effects. These effects help shape preference over the long haul so that, when a prospective student is in-market, our fast media can be more effective. Once again, it’s been well established that strong brands have more effective direct-response results. Similarly, when we make slow media choices, we value the advertising waste it may produce. Reach matters because it creates collective understanding, which once again shapes preferences and drives more positive word-of-mouth volume.

Combining Fast and Slow

To borrow from Tom Roach, higher ed brands should seek to create long-term brand communications that are engineered for immediate success. In a higher ed context, this is the marketing versus enrollment management spend or department versus degree program spend, or even to over-index on list-buying conversations. It’s also a conversation around fast and slow media. Depending on media choice, we must understand that the media we choose and the effect we hope to have reside on different timescales. What’s helpful is that we have plenty of data about finding this balance.

The rule of thumb or starting point is to distribute 60% of the budget to broad-reaching, brand-building media and 40% of the budget to short-term, direct-response media. If the category skews toward low involvement, more budget should be given to fast media. If the category is a more high-involvement category (i.e., B2B or higher ed), 50% to 70% is the sweet spot for slow media. Of course, as with all marketing, there’s a caveat: the balance will ultimately depend on media spend, scope and an organization’s level of comfort with finding this balance. What’s certain, is that to drive sustainable growth, marketers must get comfortable with two-speed planning: the immediate and the long-term or, better yet, the fast and the slow.

Newsletter Sign up!

Stay current in digital strategy, brand amplification, design thinking and more.