Read the full transcript here:

Kevin Tyler:

Higher Voltage is brought to you by Salesforce. Today’s higher ed marketers face new challenges and must expand beyond traditional tactics to engage their many audiences. Learn how Salesforce empowers institutions of all sizes to unify first party data, build and measure targeted campaigns and deliver personalized messaging across channels. Visit salesforce.org to learn about how Salesforce can help your college or university achieve its goals.

Kevin Tyler:

Hello, and welcome to Higher Voltage, a podcast about higher education that explores what’s working, what’s not and what needs to change in higher ed marketing and administration. I’m your host, Kevin Tyler. Welcome back to higher voltage with my friends, TVP, Teresa Valerio Parrot and Erin Hennessy with TVP communications. This time we’re talking about basically a hot topics episode, where we have found some items in the news that we found to be kind of interesting and wanted to have a conversation about. And we’re just going to have kind of a round robin situation where we talk about the article and what our thoughts are on that. Erin, would you like to kick us off with your article on micro colleges? Just giving us a brief overview of what the article is about and then we’ll have a short conversation about it.

Erin Hennessy:

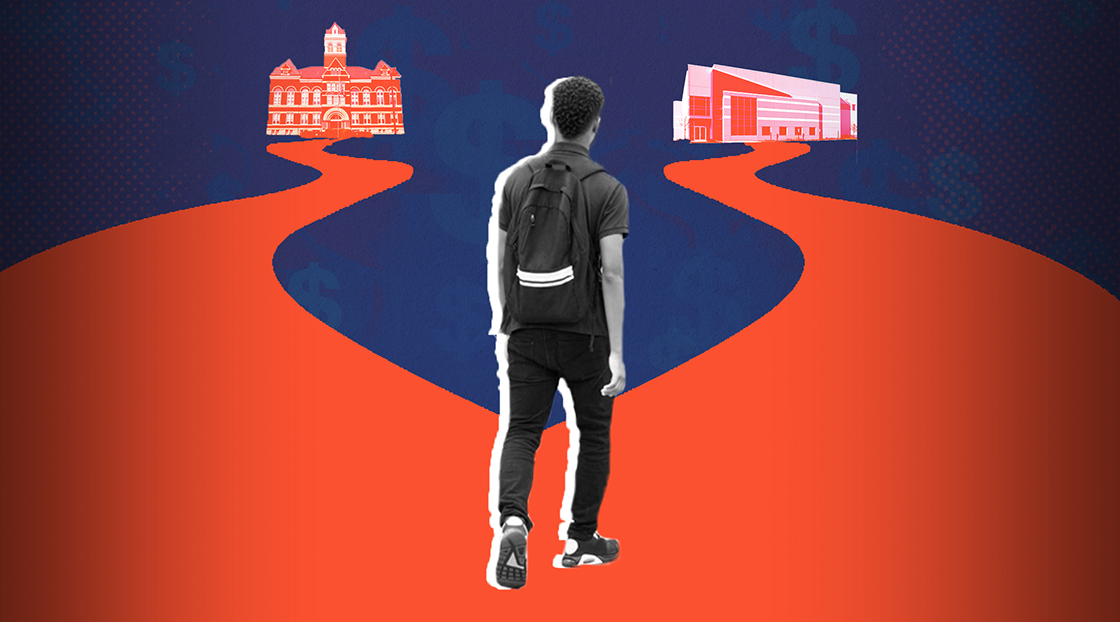

Yeah, absolutely. Thanks for putting me up first, because there’s nothing like pressure. I was really fascinated by an article in the Chronicle of Higher Ed last week and that would be August 17th. It was written by Lee Gardner and Audrey Williams June and it really focused on the pressures that are facing the very small colleges and universities, those that are around a thousand students and smaller and the pressures coming from a variety of factors including enrollment challenges, demographic cliff challenges, and sort of the very perilous fiscal path that lies ahead of these institutions, the sort of big peril being eventual shutdown. And it was just really interesting to see folks focus on this segment of institutions. It’s where Teresa and I do a lot of work. While we work with a wide range of institutions, many of them are small, many of them are religiously affiliated and many of them are very much on the brink.

Erin Hennessy:

And I think what fascinated me about this article is that it made a point that Teresa and I make in these conversations regularly that there are a number of institutions that were on the cliff’s edge in February, 2020. And not that I think any of us would ever say we welcomed or enjoyed the pandemic experience, for many of these micro institutions it was a godsend because it led to CARES Act funding, which gave these institutions an enormous, relatively speaking, enormous financial influx that enabled them to get through the pandemic, but also to really refill the coffers in some other areas of the institution as well.

Erin Hennessy:

And so I just thought it was really, really interesting to see this segment of institutions called out, really defined and have their challenges laid out in front of them. I think we talk so often about the bigger, the name brand, the more elite, to use a term, I think I’m already over, the highly rejective institutions. They take up so much bandwidth in our conversations and to see these institutions, which aren’t better or worse but are just simply because of a variety of factors, in a really tough position. To see them called out and their challenges and their hopes and their aspirations enumerated was really interesting to me.

Kevin Tyler:

This was a great read for me as well. I think there are a lot of points that I’m excited to chat with you both about. The first though, is the figures for schools of this size in 2010, were at 395 and in 2020, there were 435. And so that’s also an indication about the numbers of people who are leaving, not going, whatever else, if the number, the population of this type of school is growing. And I think that is some sort of indication of coming turmoil as well, because now there are more schools that are facing these really tough challenges who may not have anticipated being a school of a less than, of a thousand people or less in February of 2020.

Erin Hennessy:

Yeah. And I think a lot of those institutions in February, 2020 were more than likely grappling with the really hard questions of do we merge? And if so, with whom? Do we do a strategic alignment? And if so, with whom? Or do we start to think about a shutdown? Our experience has been that that question is the one that is most often not discussed and really needs to be because there is such a narrow window for an institution to execute a responsible step away from freestanding to either a merged, acquired situation or a shutdown. And so many leadership teams, presidents and boards, I lay responsibility equally on both of them, are so reluctant to have the conversation that they miss that window to execute a responsible shutdown.

Erin Hennessy:

And the trauma of that process, which was already going to be considerable is just amplified because it is done too late. It is done without sufficient forethought. Because I’m a communicator, I will say it’s done without sufficient communication. And it simply doesn’t have to be as disruptive. It’s going to be disruptive, but it doesn’t have to be as disruptive to students, faculty and staff, as it is simply because it’s a really scary question to contemplate.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

Erin and I wrote a piece before the CARES Act passed, where we were asking presidents and boards to have those really difficult conversations because without that CARES Act money and especially as we saw the institutions were hemorrhaging money and enrollment, that was the right time to be having that conversation. And my big concern is the CARES Act money just frosted over that layer of the cake and we moved on. And those conversations and those critical questions were never asked and never discussed. And that makes me wonder for this 435, what that means.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

And Kevin, I do think it’s interesting that we gained 40 additional institutions that are in that micro college space, because I would be curious to see what their enrollment trends look like. Because if this is a steep drop to get you into this micro college world, what does that mean? And are you having those conversations about what comes next? We’ve worked with institutions, as Erin mentioned, that have closed and we’ve worked with some that have merged and you get to choose your own adventure. You get to choose what that is like, but only if everybody is willing to think about the responsibility that they have to those faculty, staff and students for an education or as an employer and what those next steps look like.

Erin Hennessy:

And just one last point that I’ll throw in there, Teresa’s absolutely right. The CARES Act money was a godsend and a lifesaver for a lot of these institutions. I am going to go way out on a limb here and say most of the institutions for whom this money was a godsend and a lifesaver did not take this extra time to figure out how to address the systemic issues undergirding their financial position while they were bringing in CARES Act money. So those systemic issues are still going to be there. And once that CARES Act money runs out, I am guessing that you are going to be as an institution back in this spot where you need to be having these really hard conversations because you haven’t addressed the underlying issues.

Erin Hennessy:

And granted you’re managing a pandemic. You were trying to keep the lights on and the doors open and people employed. And I get that, but at some point that money runs out and the hard questions are still there. And so using this time while you’ve got a little bit of a financial cushion to think about how you’re going to have those hard conversations and what the ideal outcomes of them are, is a really important thing to be doing right now.

Kevin Tyler:

One of the things that struck me about this article and I am still, as I’m talking about this, trying to decide if it’s worth bringing this up, but I think it’s important enough to do it. So I’m going to do it. But later on in the article, it feels like there’s a population of schools that is just kind of left out of this article. And I think that in those schools are the HBCUs. There are some other schools that, there’s this whole chunk of the article in the middle that talks about the beginning of American higher education. Every college is tiny and then numbers of people who went to school and then numbers of people who were going completely leaves out this other history of higher education that is so glaringly absent in this article. And so it raises a lot of questions about these schools that are in the micro college community now and what got them there, to Teresa’s point.

Kevin Tyler:

We’ve seen this. One of the articles that I’m bringing is this piece about Black enrollment and how that has dropped and is that Exodus part contributing to these other schools kind of sliding into this community? And if we’re not telling the whole full story at every opportunity, especially around higher education, people might not really understand the full entire history of higher education. And so that part of this article was challenging for me because there is a whole other story and a whole other track of information that feeds directly into what we’re talking about here.

Erin Hennessy:

You’re 100% right and since you haven’t done it, I will do it for you and plug your conversation with Adam Harris a couple weeks ago, which was absolutely spectacular. Having read the book, having heard Adam interviewed in a couple of different places, your conversation with him went into parts of this issue and parts of this history that other folks didn’t. And no knocks on Terry Gross, but you got to places that she didn’t in your conversation with Adam. So I really encourage folks to both listen to that and to read his book, The State Must Provide.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

And I would say, I think you raised an interesting point, Kevin, because this does go into, for example, women’s colleges and what that trajectory has looked like and why some of them have closed and some of them have reemerged and what that means. And it goes into and includes Antioch College in this story and some of those more famed, if you will closures and resurrections. And I do think it’s a really important time for us to be thinking about where are the HBCUs and what does this mean for them? Because they aren’t immune from some of the challenges that we read about in this article. And having said that, they’ve actually succeeded for this long with so many fewer resources that what can we learn on the positive side of what that looks like and how you stretch a dollar further than you ever thought that you could stretch it.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

So I think there are some institutions for us to be thinking about. Kevin and I had a conversation last week where we were saying, and wouldn’t it be nice to be talking about community colleges and some of the regional institutions and some of those that if you look at what their drop in enrollment would be on a percentage basis are finding themselves grappling with some of the same conversations that these micro colleges are facing? What can we learn from all of them? And how do we start to tell a story about higher education than is more than just the usual suspects?

Kevin Tyler:

Right. Exactly.

Erin Hennessy:

And I think Teresa, you raise a really important point in terms of talking about lessons learned and what we can take from institutions in this category. I think it’s worth pointing out that there are some institutions in here that are at 975 students or 1000 students flat that are fine, that are doing well, that are very aware of and comfortable in and secure about who they are as an institution, who they serve, what their mission is. So not every micro college is a story of peril, but there are I think, lessons to be learned about how do you articulate a mission that really speaks in a compelling way to your audience who wants to participate in your educational approach? And how do you manage expectations that some folks have that we are always going to be in a growth mindset?

Erin Hennessy:

You are only good if you are continuing to grow, if all of your numbers are continuing to increase. Some of them, yes, absolutely need to increase, but some institutions are very content at 975, they can fill those seats and they don’t want to grow into the next fill in the blank. They want to be the current fill in the blank and they’re very comfortable there. So I do want to make sure that we point out this isn’t always a horror story. Sometimes it’s a really good story of a really great institution with a really well defined mission that is doing great work for a really defined set of students.

Kevin Tyler:

Yeah. And I think it’s important to point out, obviously that like you just said, that not every school wants to be huge. Not every school’s trying to get bigger. They just want to be who they are when they need to be and serve students the way that they serve them. I think one of the interesting parts of this article to me was the mention of the hesitation of parents when they understand that there is a college that feels like it’s on precarious ground as one of these micro colleges. And it brought to mind this idea that I learned from the story about the Isabella, the Gardner Museum heist, and how if a museum is robbed, the museum is likely not going to say that we’ve been robbed because then that hurts the pipeline for the other people who want to donate art to it.

Kevin Tyler:

And I think it’s similar in higher ed where people don’t want to talk about yeah, we’re hurting. We don’t have enough students. Our faculty are leaving. We don’t have enough money. Those are not the kinds of conversations you want to have with prospective families. And so what does that mean for the marketing efforts and the communications efforts like we talked about in the last episode, about being truthful and authentic about what’s happening on your campus? What does this mean for these tiny schools who are up against the ropes in very, very precarious ways?

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

I think that it actually leads into an article that I shared with both of you. And I think this article was by Jon Marcus writing for The Hechinger Report and it’s how higher education lost its shine. And I think part of that is this story that we have told about higher education and what it means for graduates isn’t holding up the way that we always had it hold up. Jon does a fantastic job of going through talking about different groups and how they think about higher education, pulling it apart, whether it’s by political sector, by a number of different factors. And it includes how students are thinking about us as they’re choosing not to enroll.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

We’ve seen so many of these articles come out that say people aren’t enrolling and here’s why, and it’s this one demographic, it’s this one piece, it’s this one part. And I think what really just made me stop and read Jon’s piece twice is he pulled together all of those different data points that say you don’t have the reputation that you had before and you can’t rely on what it was that you brought to the table once upon a time. The economic mobility aspect of this isn’t enough. The legacy aspect of this isn’t enough. All of the different ways that we talk about the worth and the value isn’t holding water with parents or with students, and what does that mean?

Kevin Tyler:

Yeah. This was the fascinating article that kind of made the rounds at my agency. First of all, the sheer percentages that are listed here in these states are astronomical. So there’s that argument that we have to pay attention to, but also the kind of repositioning of what competition looks like in higher ed. It used to be, it’s just other schools and our competitors are the school down the road and the ones in California, wherever it is.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

Wherever you had cross apps, right? Wherever you had…

Kevin Tyler:

Exactly.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

You had cross apps or whoever you used as your competitive set for your accreditor. That’s how we kind of thought about what competition looked like.

Kevin Tyler:

And we now know that that is, those aren’t the only people who are competing with higher ed. We’ve known that all the time, but there’s now a larger conversation to be had around where these people are going to get what they need to be competent employees. And the employers are delivering that. And so we now need to think about competitors not just being the whatever other schools, but also the Googles and the TikToks and the Apples and the whatever else, because the argument of the investment, as you just said, Teresa does not hold up to the paying off of and what you’re getting paid out of school. There are too many questions being asked about the value, and this is more of the same we’ve seen for so long in this conversation, but I just think it requires higher ed to reposition itself or reformat itself to attract a far larger kind of person or far larger population of people than traditionally old and traditional.

Erin Hennessy:

What’s so disheartening about this piece and I agree it was excellent and I hope is being shared in cabinet rooms, but also with board members across the country. What’s so disheartening and maybe I’m just in a cynical mood today, is that this is going to lead to another round of all of us sitting in very large ballrooms at higher education association meetings and having,, watching presidents get up and say things like, “We just need to do a better job telling our story.”

Kevin Tyler:

I think you’re exactly right.

Erin Hennessy:

Honestly, we have been listening to that for years and at no point do I think we’ve gotten any closer to understanding that the story we’re telling isn’t working anymore. It isn’t a storytelling problem. It is an innovation problem and a programming problem and a flexibility problem. We are continuing to expect students to just fit themselves to our models and our timetables and our programs and our outcomes. And we are not doing the hard work, the scary work, the work that gets us criticism from our faculty and from our board to rejigger what we’re offering. It’s not a storytelling problem. It’s not a communications problem. Teresa and I say this all the time. If I had a dollar for every time we say this, “I can only communicate what you give me to communicate.”

Kevin Tyler:

Right.

Erin Hennessy:

I can’t move the needle on this issue unless the institution is willing to do something different and give me a different story to tell.

Kevin Tyler:

Right.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

Yeah. There’s a data point in here that backs that up Erin and that is the proportion of 14 to 18 year olds who think education is necessary beyond high school has dropped from 60% to 45%. And more than half of teenagers who are planning some further education, say they are open to something other than a four year degree.

Kevin Tyler:

Exactly.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

They want something. What they’re telling us is it’s not what we’re offering. I think that we need to be thinking about that first in making some very significant shifts in how we think about students, how we think about offerings, how we think about packaging. All of the different things. And not in gimmicky ways, because I think to Erin’s point, that’s where we saw a whole bunch of gimmicks was after the last round of let’s talk about the value of higher education and let’s talk about ourselves differently, that didn’t really fundamentally change what we were offering. So using your Kodak example, we moved from a full on camera to an Instamatic. And that wasn’t enough of a shift to where everybody is.

Kevin Tyler:

Yeah. I firmly agree with you about what was being offered, but how are we telling that new story? I think that we can’t even change vernacular at higher ed. We’re still saying traditionally aged. Well, we all know that’s not exactly traditionally aged. We’re still using majority underserved. Why can’t we make the evolutions that are necessary to make even small changes in the conversation around higher ed, let alone the big offers and programs and what people need. It’s this idea that what we have done all of this time is going to be, we just stay the course, we will be okay.

Erin Hennessy:

We have consistently heard calls from lawmakers, policymakers, parents, students, alumni, that higher education needs to innovate. Higher education needs to do something new. Higher education needs to be responsive to the workforce, to the interests of students. And all of these things are accurate. And then institutions go out and they attempt to innovate and they try and do something new and they get dragged for it. If it doesn’t work flawlessly from jump for less money, again, reason number 675,000 why I’d never consider a higher ed presidency.

Erin Hennessy:

It’s an impossible task because your law makers are telling you, “You need to be able to offer a degree for $10,000.” Okay, well then I’m going to cut the climbing wall, the residence halls, the mental health counselors, the dining hall options, no oat milk for anybody. And all of a sudden the parents are going to come and absolutely run you out of town on a rail because you aren’t providing the experience that they want for their students. And so it’s this constant catch 22. If we need to be different, we need to be better, we need to be nimble, we need to innovate. But you better do it right. You better do it right every damn time. And you better do it right for less money and fewer resources. It’s absolutely impossible what we’re asking these institutions to do.

Kevin Tyler:

I agree with you. I agree with you.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

I also think though, Jon points in describing the data, he’s also pointing to some of the small changes that can be made as well as some of these big fundamental changes. And I think so often everybody throws their hands in the air and says, “Oh, but this is such a big problem.” Well, there are some incremental steps that we can start thinking about and there are some ways for us to be moving that needle so that it just isn’t well, it’s all or nothing. And what does that look like? Because part of that is student focused and part of that is community focused. So as we talk about the demographic cliff, what does it look like when the number of traditional age students declines? What happens to enrollments? We still have a lot of options out there for who can fill our classrooms.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

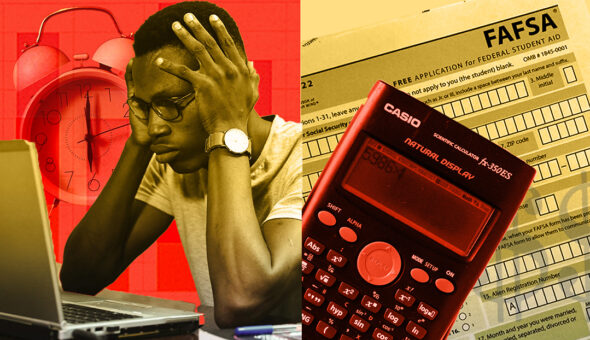

It’s do we want those students and are we prepared to accept them into our classrooms and have them succeed? So Kevin has his two articles, I’ll add my last one. My last article was from the Education Trust and it was a report that’s entitled For Student Parents: the biggest hurdles to a higher education, should be degree, are costs in finding childcare. And if you think about what that means, we have student parents out there who are traditional aged and who aren’t that we could have come in, but they can’t afford to come. And if they can’t afford, they can’t arrange the childcare to succeed. I’m not saying that higher education needs to be responsible now for daycare centers and for making sure everybody has a place for their children, but there are some ways and steps that we can be thinking about this especially as we say, we’re going to be looking at additional student populations to make sure that we’re filling our classrooms.

Erin Hennessy:

Especially as we can expect to see some increase in student parents as Roe V. Wade is rolled back.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

Right.

Kevin Tyler:

That’s exactly right.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

And we have students who are still going to want to enroll in states where abortion care is now going to be completely restricted, as well as states where it is going to be rolled back.

Kevin Tyler:

That’s exactly where I went to as well. Exactly.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

As we say, what about the different states? The study found that there is no state in which a parent can work 10 hours per week at a minimum wage job and afford both tuition and childcare. And if you stop and think about that, there’s nowhere in this country. And if you start to think about it takes 52 hours per week of a student parent to work to cover childcare and tuition costs, how do you work 52 hours per week and be a parent and go to school? We’re asking for the impossible.

Kevin Tyler:

Right. I do want to give a shout out to John Comerford president of Otterbein University in Ohio, who was referenced in the How Higher Education Lost Its Shine article for other reasons, but on that campus specifically, and I know this because he’s been on the show before, they use their early child development students to provide childcare to the adults who come in for night school at Otterbein and they can just take their kids there. And it’s not a revolutionary idea. You’ve got people who are doing this, you can give them some practical experience doing it. But when we have articles like this around childcare being the number one expense that keeps people from getting a higher education, what are some of the solutions that are like the one at Otterbein that we can employ to help people get to where they’re going? I’m flummoxed by the entire thing.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

Again, sometimes it’s the big solutions and sometimes it’s the small solutions, but if we’re not looking for solutions, we’re not going to see them.

Erin Hennessy:

Yeah.

Kevin Tyler:

Yeah.

Erin Hennessy:

I think childcare is particularly challenging. Teresa and I have worked with institutions that have had to make very challenging choice to close childcare centers on campus that have been offered primarily to faculty and staff below market rate in areas where there are, it’s highly rural. There are very few other options. Thinking about the licensure and insurance requirements on those centers can be staggering. But I think Teresa, you make a great point about incremental steps. Where can you find some way to bridge that challenge that isn’t perhaps necessarily a full blown childcare center on your campus, but can you make connections with organizations in the community? Can you work together with other employers of size because I think in a lot of communities we are among the largest employers, to find ways to help folks access those kinds of services without taking on that enormous legal and financial responsibility?

Kevin Tyler:

I do think things like this, programs, initiatives like this do contribute to the difference between being student centered and otherwise, and not student centered. And if you don’t understand what your students need and where they’re coming from, it’s harder for you to get them to where they’re going. That’s how I look at it. In terms of along those same lines, I guess I should say my articles, first one is about super HSIs. HSI is Hispanic serving institution. Currently federal government requires a campus to have about 25% of their student body to identify as Hispanic, to unlock grant dollars and other benefits. And an article that was published a while ago, actually in March of this year, which has kind of stuck with me and I’ve shared with some of my clients who are HSIs or who are looking to become HSIs talks about how that measuring stick is fairly superficial and that there should be more responsibility in the service of the students, not just a threshold to reach which I am a firm believer in. I’m curious about your thoughts on this article and any other perspectives you might want to share here.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

I was lucky enough to be on a team for Lumina Foundation that visited a number of HSIs as well as HBCUs. And what we were looking for was to see what were their metrics of success and how could we share those with other minority serving institutions at large, and as well as predominantly white institutions, but especially making sure that we were sharing those with minority serving institutions. And to your point, it’s such a superficial measure to say, this is how many we brought in. It needs to be, how are we retaining and how are we keeping students moving forward? But I would guess as the different measures were being developed, there was pushback on what that would look like and how exactly to implement that. And as we sometimes see in policy, we end up going for what seems like a simpler policy option, but it doesn’t benefit students in the same way.

Kevin Tyler:

Totally. Which leads directly into the next article, which is about Black enrollment and how it’s been declining significantly over the last few years. Pandemic yes, is part of the contributors to that conversation, but the decline was felt before that. And in the article that I have pulled, I think it was in 2010, there were 2.6 million African American students, Black African American students. And in 2020, it was at 1.9 million. And this goes to Teresa’s last point about, it’s not how you bring people in, it is how you are serving them during their experience.

Kevin Tyler:

And again, a lot of factors kind of play into the exodus of Black students, but we have all these colleges every day asking the agency I work in, “We want a more diverse class this next time around.” And my new response to that is going to be “Well, what are you doing to retain the diversity that you have currently?” Because this isn’t about just inviting a bunch of people to your campus. It is about far more than that. And it goes back to your transactional nature of things. This is not a transaction. This is you are helping people grow and if you’re not doing that on all the aspects that they need to be helped grow in, then are you actually serving them? And I think that I could talk about this for hours and hours and hours, but I’m curious about your thoughts on this as well.

Erin Hennessy:

I just will throw this out here. I think we in higher education spend a lot of time talking about the pipeline and very little time doing anything about it. I think we expect Black students, Hispanic students to be delivered to our doorstep, and we expect to be congratulated for welcoming them in. And we forget that our responsibility does not end on census day of their first year, but instead extends through four years and if we’re smart, beyond. Because how do you then go back and fill that pipeline? By building that relationship through four years, making sure your students graduate successfully, and then making sure that you stay in a relationship with them as they go through their professional development and continue to be a good partner.

Erin Hennessy:

I just think the three of us have yelled about this over cocktails on Zoom before. It starts from the folks who we are asking to go out and market to students of color are overwhelmingly not marketers of color, aren’t institutional leaders of color. I’m not pointing a finger at marketing for being less diverse than anybody else. Academic leadership, higher ed leadership is not diverse and how we expect to reach these students where they are and make a compelling case to them for what we have to offer when we don’t understand lived experience in that way is, I just keep getting stuck on that question. And I haven’t seen anybody come up with an answer to it yet.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

So I recently had a tough talk with a president about their sense of belonging survey results for their students and the students of color don’t feel like they belong. And so the president said, “Well, I’m going to see how this compares to our peers and how their students feel that they belong.” And I said, “Honestly, I don’t care what your peers say. I don’t care what their students do. I do within that institution but for you, you need to be caring about your students and how they feel. This isn’t something that you can look from one institution to the next institution and say, our students of color, their sense of belonging is low, but that’s okay because if you look across the industry, it’s low. That’s not okay. These are your students and they are not just data points. And don’t try to normalize this and make you feel better about how you are bringing these students into your community by saying, this is what everybody else looks like as well, because I don’t don’t want to hear that.”

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

And I had an epiphany recently thinking just about, I spent a lot of time as Erin knows, playing a psychologist, even though I’m not one. And so I started to think through how do I start to help presidents and cabinets better understand what sense of belonging and what retention efforts really look like? And so I started to pull academic journal articles as well as articles. It’s interesting to me, the way they really dug into the scholarship in ways that I wasn’t getting that same engagement from articles. They skimmed the articles and had a conversation. It was very nice. But once we had this in the scholarship framework, it was a much different conversation and they almost needed to be met where their careers historically had been.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

So helping them to get the materials that would help them process and then to do something about it, I think is also a way that we need to be thinking about how we’re staffing these conversations and not letting people have a by, by saying well, how does this look for everybody else? This is about you, this is about your students, and this is about keeping them.

Kevin Tyler:

And at the end of the day, we are talking about an industry that was never built for anyone of color ever. And we are expecting people of color, students of color, faculty of color, staff of color, everyone of color, to just come show up without having done any work to fix the system that was discriminatory in the first place, without having any action.

Erin Hennessy:

And once they get there, we’d like them to carry the emotional and mental load of fixing the place.

Kevin Tyler:

Exactly. Be on this committee, be on this task force, do this. Let me ask you, is this okay? Is this picture stereotypical?

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

I was that student. I was that student…

Kevin Tyler:

I was too.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

That I learned after the fact they chose me because they had a demographic. They were looking for a Black male, a Hispanic female, and then a white male and female. And afterwards to look at where I fit, I still think about that. I still think about that I was just demographics and they loved my ’90s bangs and so they put me on the front of that alumni magazine and that still hurts my heart.

Erin Hennessy:

I am captured somewhere in the Drew University archives on the front of a brochure wearing jorts, and so your bangs got nothing on my jorts.

Kevin Tyler:

This is one of those things, I don’t even know how it were to begin to talk about this with people. That’s my only response. And the CEO of my agency, Jason Simon, at one of our recent webinars said, “Don’t come at us with any request to diversify your campuses if you’re not doing the work yourself.” And I appreciate those kinds of statements because I don’t want to do it anymore. I don’t want to do the kind of work to attract a group of people to a place where they might feel harmed or might whatever. And that’s just not what I want to do with my life or my time or any of it. I don’t want to be paid for that. So these conversations are so important because everyone wants the same thing. Everyone knows that now the currency is diversity and it wouldn’t be that if it hadn’t been for 2020. So what are we going to do about it? And that’s what I want to figure out.

Erin Hennessy:

Teresa and I wrote a piece that very much aligns with what Jason has said, talking about the inability that your team has, your communicators have to talk about your work, to diversify your institution and to make your institution a welcoming and safe place for students if you haven’t done the work. There’s no email, there’s no silver bullet language. There is nothing that can be said if you aren’t willing to do the work. And there are challenges in that work and we’ve all experienced it. Students have a much shorter time horizon than academia is suited for. If we can get a committee together and charged and have them get a report out within two years, that is a scorching pace and our students and our faculty and our staff are no longer willing to be patient and I don’t blame them, for another committee to be seated and charged and deliberate and come up with a report that’s going to be put on a shelf somewhere that no one’s going to do anything about.

Erin Hennessy:

And there is no communication that can be planned and executed that is going to take the place of doing that actual DEI work. And it is not the job of your CDO and it is not the job of your Black and Hispanic and Native students, faculty, staff. It is the institution’s job and the president needs to lead that work and make sure that it’s happening consistently across the campus. And then you get to think about communicating about it. Not…

Kevin Tyler:

I heard that.

Erin Hennessy:

Until you actually start doing the work to move that needle.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

I would push back and say, we have successfully been able to say we don’t move quickly. And then the pandemic came and everybody saw yeah, we actually can if we have to and if we want to.

Erin Hennessy:

That’s a really…

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

So we now are back in that position where we’re saying, “Oh, but we can’t do that because it takes time.” You can’t have it both ways and still expect to be viewed as credible.

Erin Hennessy:

Yeah. Well, I’m glad we solved this intractable problem from higher ed.

Kevin Tyler:

Yeah, we do good work. We do good work at Higher Voltage.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

We actually did solve a problem. I think that Kevin is now a communicator because he was just talking again about truth and authenticity. I think he’s on our side. I think we can claim him.

Kevin Tyler:

I mean, I don’t…

Erin Hennessy:

There are no sides.

Kevin Tyler:

Pick sides. There are no sides. Listen, we’re just trying to get people whatever they want. I don’t know. Listen, thank you so much, Teresa, Erin. It’s always a pleasure to have you on to get your thoughts on so many important topics. I really appreciate not just your friendship, but also your expertise, your perspectives, and being here with us today. Thank you so much.

Erin Hennessy:

Thank you.

Teresa Valerio Parrot:

Thank you.

Kevin Tyler:

That’s it for this week’s episode of Higher Voltage. We’ll be back soon with a new episode and until then you can find us on Twitter, @VoltHigherEd. And you can find me, Kevin Tyler, on Twitter, @KevinCTyler2.