For years, two archetypes were often painted about the experiences of college athletes.

The first went something like this: overworked student-athletes eating Ramen noodles and working side jobs at their college bookstores while the universities cashed in on their on-field successes, to the tune of billions of dollars.

That lived uncomfortably alongside the other: student-athletes (usually football and basketball players) at big-name schools driving luxury cars and wearing expensive jewelry no college kid could afford; where they got these things, nobody quite knew.

These two tales sketched the boundaries of an uncomfortable reality: Major college athletic programs raked in big dollars through the efforts of college athletes whose time on campus was predominantly spent working for their teams, though they could not legally be paid for those efforts beyond their tuition costs.

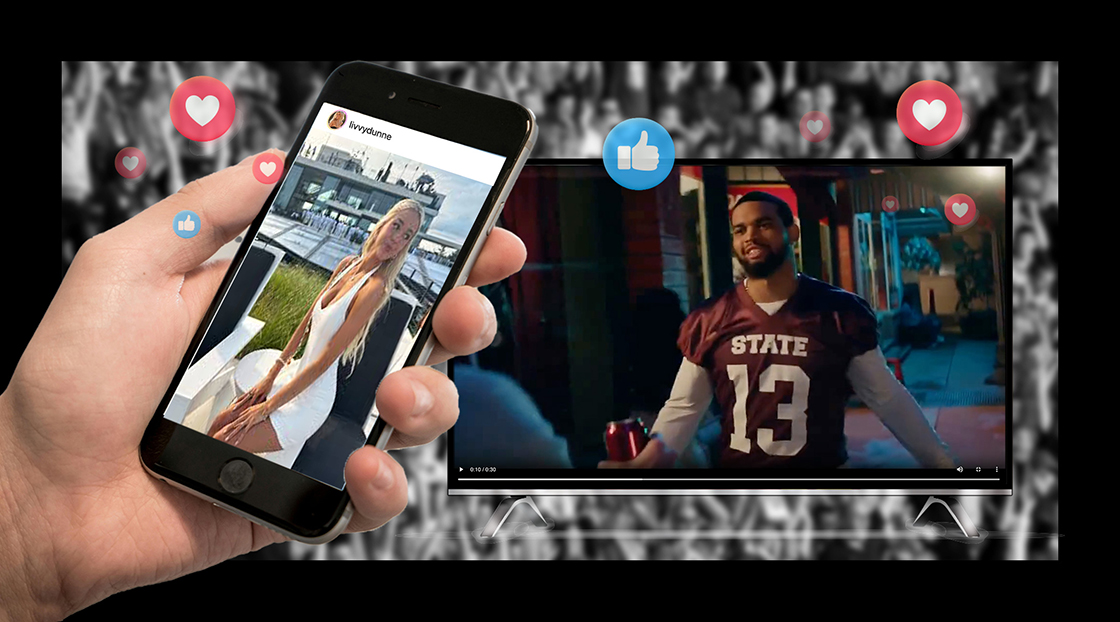

In July 2021, the Supreme Court ended that when it ruled the NCAA’s outright ban on student-athlete compensation was illegal. This paved the way for college athletes to earn money for their work by marketing their names, images and likenesses (NIL).

Now, a few thousand college and high school athletes make six figures yearly, and some three dozen are worth $1 million or more in annual endorsements.

Schools have long cashed in on their most marketable players, well before NIL gave athletes a piece of the money-windfall pie. But is there room for schools to also build on athletes’ success in ways they haven’t before? The success of LSU gymnast and social media influencer Livvy Dunne offers perhaps the greatest insight.