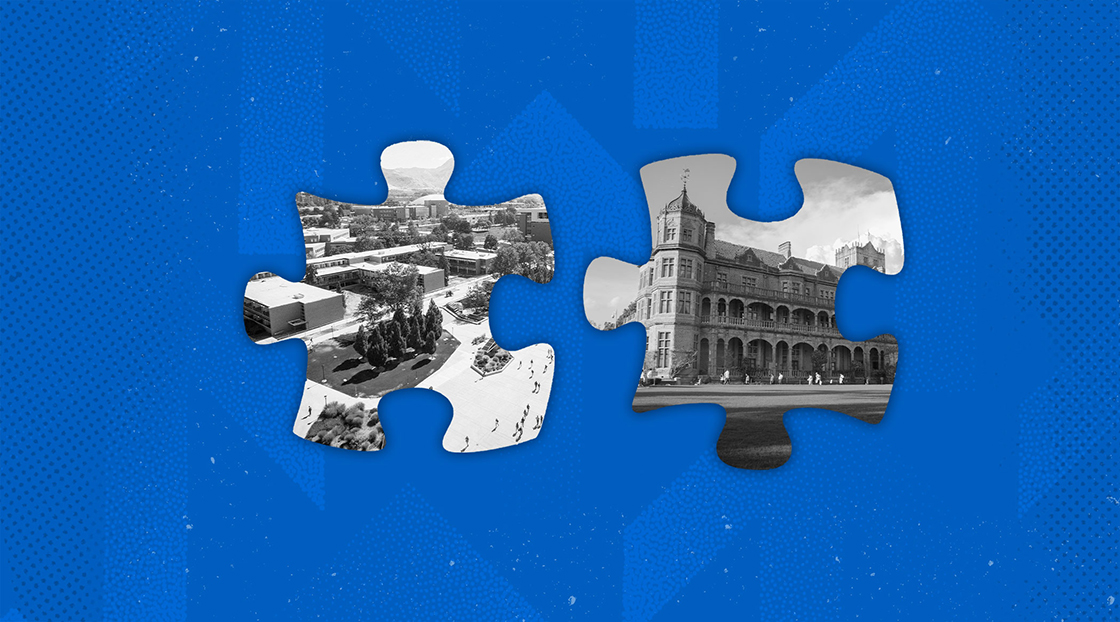

The first half of 2023 brought two notable higher ed acquisitions of for-profit institutions by nonprofits—Lindenwood University’s acquisition of Dorsey College and the University of Idaho’s acquisition of the University of Phoenix. As a result, both acquisitions have been converted to nonprofit status.

The moves on the part of Lindenwood and Idaho follow a trend over the past several years in which institutions that serve traditional students are looking to diversify by venturing into the pool of students historically served by for-profits, such as online students and career-focused learners.

Lindenwood University Acquires Dorsey College

Lindenwood University, a private Missouri-based liberal arts institution, with approximately 7,000 undergraduate and graduate students, announced in late March that its parent entity, the Lindenwood Education System, had acquired Dorsey College, a Michigan-based for-profit career college, from a private-equity firm.

Dorsey, which will retain its name and continue to function as its own institution, is pursuing recognition as a nonprofit education institution.

Lindenwood pursued an acquisition of Dorsey even though it wasn’t for sale. The acquisition was attractive because it offered the university an opportunity to move into the “just-in-time” learner space. The space has been an area of focus for Dr. John Porter, president and CEO of both the university and system, after hearing from local school superintendents that 50% of their graduates are going into the vocations.

To capture some of the local vocational students, Porter plans to build a Dorsey branch on Lindenwood-owned property in Missouri.

Porter came to the university after a career in the corporate world. Since becoming president in 2019, he’s approached his role from a business perspective. He quickly formed a mergers and acquisitions team, which he viewed as being vital to the institution’s growth strategy.

Additionally, due to the limited revenue streams traditional institutions have, he came up with a 40-40-20 model, meaning that he wants 40% of the revenue to come from traditional means like tuition and room and board, 40% from online program offerings and 20% from alternative revenue streams like LindEngage, the for-profit company the university started to provide services to non-education companies.

Porter anticipates the system will acquire additional colleges and universities in the future. “We’re looking at programming where we could either deepen our programming or provide programming we don’t have,” he said.

Some struggling institutions have seen the writing on the wall and have contacted Porter in the hopes of being acquired by the system, but he said he doesn’t feel comfortable spending institutional resources on risky bets.

University of Idaho Acquires University of Phoenix

Roughly a month and a half after the Lindenwood-Dorsey news came out, the University of Idaho announced it would form a nonprofit entity to acquire one of the first big players in the distance learning space—the University of Phoenix.

Dr. John Woods, chief academic officer and provost for Phoenix, said the previous private-equity owners of the university had been having conversations for years about having it partner with institutions that are looking to get into the online adult learning space because of the looming enrollment cliff, many of which are turning to online program managers, or OPMs.

That desire is what eventually led to Idaho’s acquisition of the university.

“We’ve been thinking about the enrollment cliff because it’s such a reality for traditional institutions serving large populations of undergraduates,” Dr. Torrey Lawrence, provost and executive vice president for Idaho, said. “We’ve been expanding our own online offerings but also looking for ways to be innovative and ready for these changes coming in a few years.”

To facilitate the acquisition, a nonprofit entity was set up and the ties with the previous owners were severed.

To some, the marriage of the two institutions seemed like an odd fit. Idaho is the state’s public land-grant research institution that educates approximately 11,500 traditional learners. Phoenix was a for-profit institution that focused on serving working adults.

“The political landscape in Idaho leaves public universities vulnerable. Meanwhile, for-profit universities are taking a hit on a national scale,” Scott Green, president of the University of Idaho, said at the time. “By affiliating with University of Phoenix, we bring together the best of both systems and build on our common desire to educate students.”

Despite the drastically different backgrounds of the two institutions, there is a precedent. Purdue Global, a public institution, finalized its acquisition of the for-profit Kaplan University in 2018. A key difference is that the 30,000 students that were enrolled at Kaplan were transitioned to Purdue. Two years later in 2020, the University of Arizona announced it had formed a nonprofit, University of Arizona Global Campus, and acquired the assets of Ashford University, a for-profit institution of 35,000 students.

Woods said Phoenix will continue to be its own institution and focus on its core audience of working adults.

Idaho will take advantage of the technology infrastructure that Phoenix has. Additionally, Idaho will benefit monetarily from the deal. It will receive an annual supplemental education funding payment of $10 million, with the expectation that the amount will increase over time.

A the macro level, you cannot have 4,000 mega universities. There aren’t enough people to go to 4,000 Southern New Hampshires.

Even though Idaho hopes to supplement its own funding through Phoenix, the university appears to be on solid footing. First-year enrollment for fall 2022 was the largest in the recorded history of the university, up 17.8% compared to fall 2021. This came after nearly a decade of either stagnant or decreasing enrollment.

Phoenix, on the other hand, isn’t what it was at its height. Woods attributed increasing competition and a shift away from two-year degrees as reasons why it no longer has the 400,000 students the institution did in the past.

“For the past couple of years, having refocused, improved our programs and student outcomes, we’ve started to grow two years in a row,” he said.

Unlike Lindenwood, Idaho has no interest in going on an acquisition spree. “We’re trying to be innovative and try to look at opportunities that come up, but no, we are not on any kind of mission to acquire or empire build here,” Lawrence said.

Impacts of Recent Acquisitions

The two acquisitions are part of a renewed focus on mergers and acquisitions in the higher education space over the past decade, explained Dr. Tom Harnisch, a higher education expert who is vice president for government relations at the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. He pointed to declining demographics in some regions of the country, coupled with a continued need for institutions to make revenue, as the driver for expansion.

Public institutions have historically been funded by the taxpayers of each state with the understanding that they wouldn’t make money but would rather educate the populace.

In addition to for-profits being acquired, he said the business model of small private nonprofits is increasingly unsustainable. For that reason, some of those institutions are looking to merge with or be acquired by other institutions, like some of the ones Porter said he’s been approached by.

“We’ve seen this in the Northeast and Midwest. It’s particularly acute in rural areas,” he said.

He noted that, when he graduated from a rural Wisconsin high school in 2001, there were 105 graduates, but now the average graduating class size is approximately 70.

“Those small schools feed into the local two-year colleges, the tech colleges, the four-year colleges and there’s just a declining pool of traditional-aged students to draw from,” said Porter. “This has really put pressure on college and university balance sheets.”

He pointed to stagnant and declining state appropriations for schools like the University of Idaho as being another motivating factor. Inflation and increasing salaries are also putting pressure on institutions.

Trend Indicative of Industry Duress

Barmak Nassirian, a higher education expert who is vice president for higher education policy at Veterans Education Success, added that it’s hard to deny that the industry is under duress.

“The whole business model for the vast majority of institutions, which was tied to geography, has been upended by the advent and broad acceptance of distance education,” he said.

A small subset of institutions has been able to recruit both nationally and internationally based on their brand strengths, whereas most institutions have targeted their natural markets based on attributions such as geography and religion.

“For the vast majority of institutions, where they were located essentially defined where the vast majority of their enrollment would come from,” said Nassirian. “The internet and distance education have changed that.”

Even though most of the traditional nonprofit institutions that are acquiring for-profit entities are largely doing so to generate additional revenue, Harnisch hopes the focus will be on providing a high-quality education to students.

“We’ve seen many scandals, particularly in the for-profit space, and we don’t want these institutions to tarnish their image by providing shoddy programming under their banner,” he stressed.

He’s curious to see how the state will monitor these previously for-profit entities, particularly student outcomes.

Nassirian views the acquisition of for-profit institutions by public ones skeptically, noting that public institutions have historically been funded by the taxpayers of each state with the understanding that they wouldn’t make money but would rather educate the populace.

There may be ways in which being absorbed by another institution, creating some shared cost opportunities and reducing some of the overhead could make an otherwise unsustainable institution manageable

“The model that’s emerging is that public institutions under the pressure of insufficient funding have struck upon this kind of Faustian bargain where they’re basically going to engage in predatory practices against an underserved, often minority, population in order to make money, which they will then nobly spend on their residential students that often come from middle and upper-middle-class families,” he said. “It’s a very upside-down financing model where the poor end up subsidizing the better off.”

The Lindenwood acquisition and formation of the education system, on the other hand, Nassirian noted could get at the inherent inefficiency that smaller institutions face related to the economy of scale.

“Things cost more when you’re distributing the general expenses of running an institution across a much smaller number of enrolled students,” he said. “There may be ways in which being absorbed by another institution, creating some shared cost opportunities, reducing some of the overhead could make an otherwise unsustainable institution manageable.”

Other institutions that are looking to reach non-traditional students but want to do so on their own instead of acquiring another institution should proceed cautiously, Harnish advised.

“They have to be strategic and understand their market and their prospective student,” he said. “There’s certainly a market out there for providing high-value programs in certain areas.”

However, he said, they may face difficulties.

“The online marketplace is crowded,” said Harnish. “Some institutions may not get the return on investment they’re looking for because the market can only take on so many providers. Smaller online entities are going to have to compete with larger ones that have very substantial advertising budgets.”

Nassirian explained the allure of being the next Southern New Hampshire University is tempting for many institutions.

“Everybody thinks if only I had a platform and began advertising a few tens of millions of dollars on TV that I could go from being a geography-bound institution to a mega university,” he said. “The problem with that of course is that, at the macro level, you cannot have 4,000 mega universities. There aren’t enough people to go to 4,000 Southern New Hampshires.”

He added that institutions should keep in mind that they don’t get to expand into new areas without to some degree compromising what has historically made them distinguishable.